Tacoma’s Historic Japantown: An Overview

III. World War II and Forcible Removal

As the 1940s dawned, the number of Japanese-owned enterprises had reached an all-time high of 181. The region’s growing numbers of shipyard workers and the construction crew for the U.S. Army’s McChord Field provided a boost to Nihonmachi’s customer base.

Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941 brought shock and confusion to the Japanese residents of Tacoma, as with many other Japanese communities in the United States. Issei community leaders, including the Japanese language school principal Masato Yamasaki (1873-1943), were arrested by the FBI. Sixty-five Issei-owned businesses placed advertisements pledging American loyalty in the two major English-language newspapers, the Tacoma News Tribune and the Tacoma Times. On December 14, 1941, Tacoma’s mayor, Harry P. Cain (1906-1979) spoke publicly on behalf of the Japanese, the only mayor of a major West Coast city to do so.

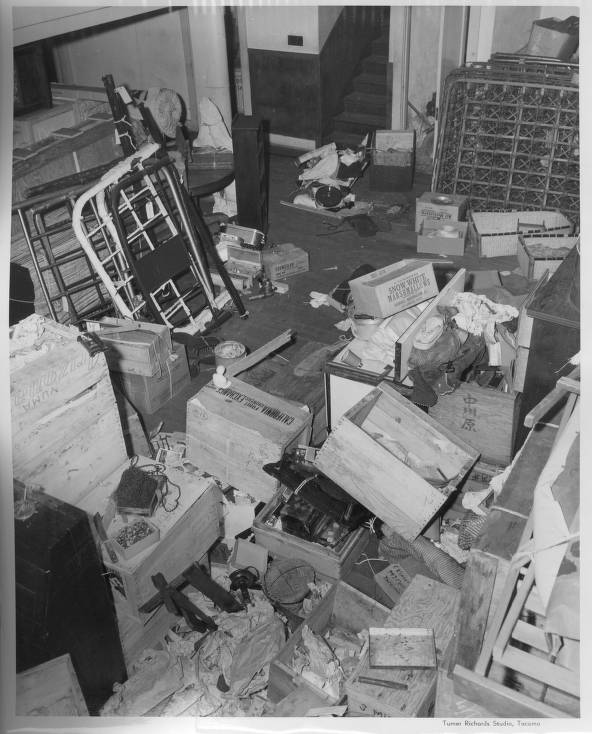

Two months later, President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945), issued Executive Order 9066, which authorized local military officials to issue exclusion orders mandating that both Japanese-born immigrants and Japanese American citizens on the West Coast be sent to inland confinement sites in remote, desolate locations. With little time to settle their personal and financial affairs, most Tacoma Japanese stored their belongings in the basements of the Japanese Language School, the Buddhist Temple, and the Whitney Methodist church. The language school became the “Japanese Community Center,” the point of registration for most Tacoma Japanese residents before they were shipped to Pinedale, a temporary assembly center in California. From there, they were sent to one of two sites of incarceration: Minidoka, Idaho, or Tule Lake, California.

After the war ended, relatively few Japanese returned to Tacoma — only 174 out of 872 residents. Some, like Uwajimaya’s owner Fujimatsu Moriguchi, decided to relocate to Seattle. While in camp, some worried about a return to their hometown after reading reports of anti-Japanese sentiment in Tacoma’s English-language newspapers. A few returned because they felt it was still home. Many who did so found that their belongings had been vandalized or looted.

*Text reprinted from Tamiko Nimura, “Tacoma Neighborhoods: Japantown (Nihonmachi)—Thumbnail History,” HistoryLink.org, 2016. Sources for this overview are listed with the article on HistoryLink.

Photo credits:

Northwest Room at The Tacoma Public Library, Image No. D-12799-10.

1945. Northwest Room at The Tacoma Public Library, Image No. D-18994-2.